I’ll admit it right from the start: I’m a Dan Brown fan. Always have been. I know, I know - it’s not the coolest literary confession a bookseller can make. Critics have sharpened their pens on his prose for two decades now, gleefully pointing out the clunky metaphors, the cardboard villains, the cliffhangers that multiply like rabbits. And they’re not wrong. Dan Brown is not a literary genius. But he tells a great story and sometimes, that’s exactly what a reader wants and at Chapters Bookstore Dublin we live to give the reader what they want!

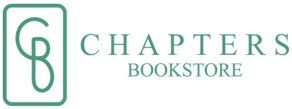

There’s a reason The Da Vinci Code, Angels & Demons, and now The Secret of Secrets have sold by the tens of millions. A Dan Brown novel isn’t about exquisite sentences or psychological subtlety - it’s about the delicious click of the puzzle-piece plot. It’s about the page turning itself. It’s about that irresistible “what if?” that keeps you reading at 2 a.m., half-mocking yourself, half-hoping you’ll wake up knowing something the Vatican doesn’t want you to know.

Why we love a good “bad” book

Literary theorists of popular fiction - John Cawelti, Janice Radway, Tzvetan Todorov - would tell you that genre fiction survives because it meets certain deep, human needs. Crime fiction reassures us that chaos can be solved; romance promises that loneliness can end; thrillers like Brown’s assure us that meaning is there, hidden in plain sight, if only we can read the signs.

Popular fiction works not because it’s new, but because it’s recognisable. The pattern is the comfort. We know there’ll be a mystery, a chase, a revelation - but we still want to feel clever for spotting the clues before the hero does. Brown understands that need perfectly. He gives us the illusion of scholarship and the thrill of discovery without demanding the PhD to enjoy it.

The secret ingredient: Blythe Brown

That sense of depth and intellectual scaffolding in his earlier work - particularly Angels & Demons, The Da Vinci Code, and my favourite, The Lost Symbol - owes a great deal to Blythe Brown, his first wife and long-time research partner. Blythe, an art historian with a background steeped in medieval symbolism and Renaissance iconography, was more than an editor; she was the architect of credibility. She dug into archives, cross-referenced obscure manuscripts, and ensured that even Brown’s wildest leaps had a factual foothold.

I miss her influence. The newer books, including The Secret of Secrets, lack that same scholarly backbone. The research is still there, but it’s lighter, more digestible - less dissertation, more dinner-party anecdote. That said, it’s still fun. You close the book with at least three new historical facts, a few philosophical questions, and a faint sense that your IQ has gone up by two points.

A personal history of hidden histories

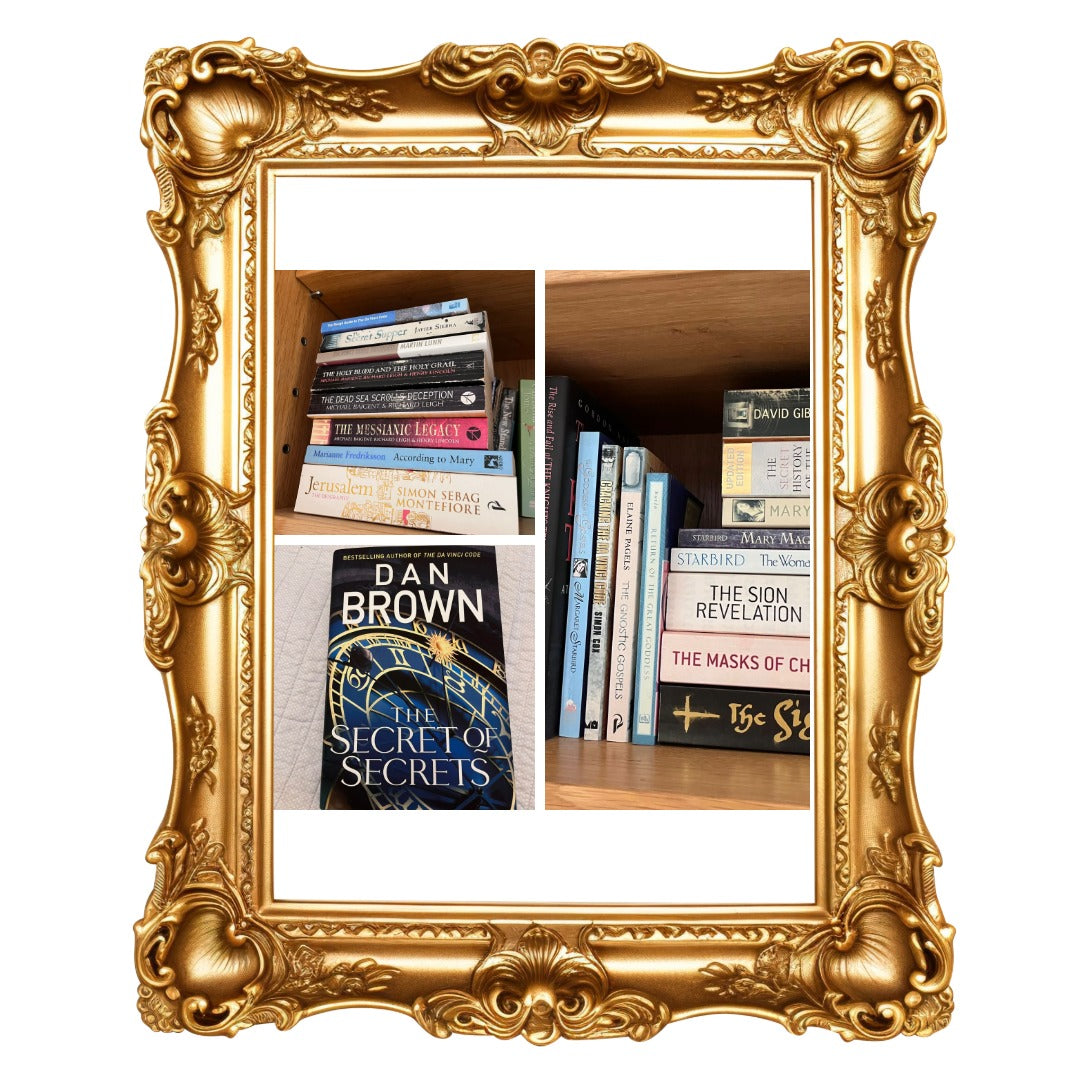

My affection for Dan Brown’s brand of symbological sleuthing goes way back. Long before The Da Vinci Code came along, I was the teenager devouring Holy Blood, Holy Grail by Baigent, Leigh, and Lincoln - that heady blend of biblical speculation, Templar lore, and hidden bloodlines. I loved the idea that history wasn’t just what the textbooks told us; it was a palimpsest, with secrets written beneath the surface.

Add to that my upbringing around Freemasons - not the global-power-conspiring sort, but the Rotary Club kind, organising raffles and restoring church roofs - and you’ll see why The Lost Symbol was my catnip. Those mysterious symbols, the beautifully constructed buildings, the sense that not everything was known, that there was more to see if only you learned to read differently. Brown tapped into that instinct perfectly: the belief that knowledge is both a burden and a key.

Conspiracies, codes, and cleverness

In my twenties, I devoured Picknett and Prince, the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Gnostic Gospels, and everything about Mary Magdalene that the Church might prefer we didn’t read. I’m not a conspiracy theorist - I just love the idea of layers. Of meaning that isn’t obvious. That’s what Brown captures so well: the tantalising possibility that the world hides messages in its architecture, its art, its stories.

For a more literary take on that premise, of course, there’s Umberto Eco’s Foucault’s Pendulum. Eco, an actual professor of semiotics (the study of signs and symbols), wove a masterwork of paranoia, intellect, and irony - the “grown-up” version of The Da Vinci Code. Brown took that scaffolding, stripped it of its irony, and gave it a pulse. He didn’t invent the symbologist hero; he made him a bestseller.

The Secret of Secrets: same formula, bigger questions

Brown’s latest, The Secret of Secrets, returns to familiar terrain - an ancient mystery, a modern threat, a coded truth that could change everything. It’s a fluent, fast-moving read, his best-paced book since Inferno. The bad guys are satisfyingly bad; the heroes flawed but noble. Yet there’s enough moral ambiguity to make you stop and think. Some of the characters do terrible things for what they believe are good reasons, and Brown - to his credit - lets us decide where we stand. It’s nice, to be treated like grown-ups.

I’ll confess: I’m still not sure what happened to poor Pavel. Perhaps I blinked and missed it, but by the end, as the narrative hurtled toward its big reveal, there was a faint sense that even Brown himself was ready to close the case and go home.

But just as I began to think he’d run out of surprises, a new thread emerged - a philosophical one. Brown suggests that our obsession with online worlds and social media isn’t an escape from reality but an immersion into another one - a kind of bodiless consciousness. It’s a big, almost metaphysical idea that feels like it belongs in another novel entirely, but it lingers.

Serendipity, synchronicity, and the sadness of timing

When I finished The Secret of Secrets, I found myself mulling over one of its central ideas - what Jung would call synchronicity, meaningful coincidence. Within days, news broke of Manchán Magan’s untimely death. I’d just seen an RTE clip of him with Tommy Tiernan, talking about not quite feeling part of this world, about the permeability of reality - how, as we drift to sleep or dance or drink, the edges blur and another layer shows through.

It struck me that Magan, in his poetic way, had explained one of Brown’s key ideas better than Brown ever could: that consciousness might not be confined to the body, that we exist across multiple realities at once. It sounds mad when you write it down - “non-local consciousness” - but in that moment, Magan made it plausible, and Brown, for all his commercial polish, made it accessible.

The Blythe effect (again)

And that’s what I miss most from the Blythe Brown era: the balance between fun and footnotes. The Secret of Secrets still gives you the thrill of decoding meaning, but it doesn’t quite deliver the same satisfying click of scholarship meeting storytelling. I can’t help but feel she brought the intellectual ballast that grounded the madness.

Still, Brown remains a master of the readable idea. He can take a concept like quantum entanglement or Marian theology and turn it into a car chase through Florence. His great trick is that he makes you feel clever - and, occasionally, he makes you be clever, because his books are gateways. They send you to Google, to museums, to Wikipedia rabbit holes. And if you’re very lucky, to the non-fiction shelves in the back of a good bookshop like Secondhand in Chapters Parnell Street!

Final verdict

I’m really glad I read it. Given its size, I whizzed through it in a weekend. I did miss Blythe Brown’s editing and intellect, that quieter sense of depth, but The Secret of Secrets is still a definite pick-up. It’s not high art, but it’s high entertainment, and it’s built on big ideas that linger longer than you expect.

It may not win prizes, but it will give you something else entirely: that old, electric feeling that the world is full of hidden meanings waiting to be decoded. And really, isn’t that why we read sometimes in the first place?

As an aside, The Secret of Secrets reads at times like a love letter to his publishers - Penguin Random House must be thrilled. And honestly, I like that. There’s something reassuring about a writer still so earnestly in love with the machinery of books. Random House, after all, was named for the idea that a house could publish anything - as random as it pleased. I rather like to think of us here at Chapters as the same sort of Random House: open to every story, every genre, every reader who wanders in looking for a secret or two.

![Manchan, Magan IRISH INTEREST Magan Manchan: Listen to the Land Speak [2022] hardback](http://chaptersbookstore.com/cdn/shop/files/manchan-magan-magan-manchan-listen-to-the-land-speak-2022-hardback-57197364117843_{width}x.jpg?v=1743077146)

![Keegan, Claire IRISH FICTION Claire Keegan: Small Things Like These: Shortlisted for the Booker Prize 2022 [2022] paperback](http://chaptersbookstore.com/cdn/shop/files/keegan-claire-claire-keegan-small-things-like-these-shortlisted-for-the-booker-prize-2022-2022-paperback-59373419102547_{width}x.jpg?v=1758902529)